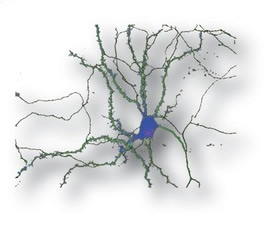

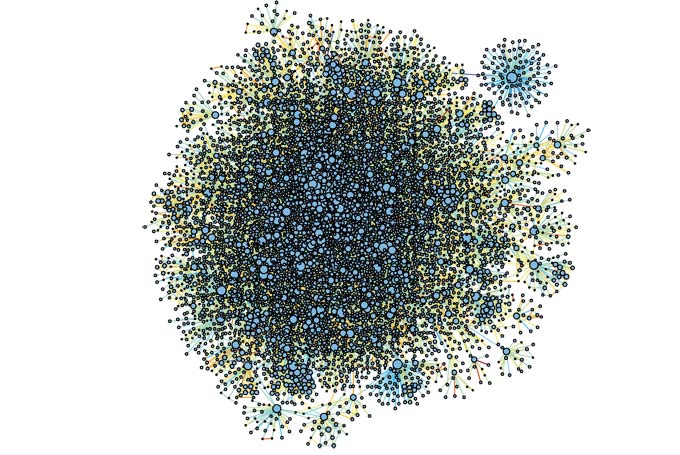

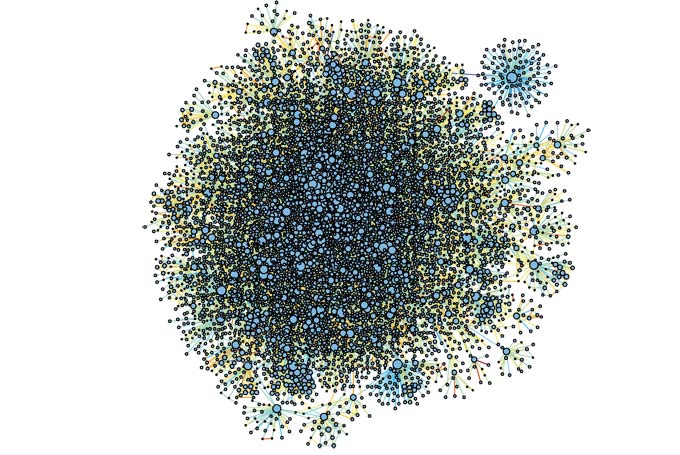

Static visualization of the social network of some of the persons speaking by phone (300,000 customers). Each circle is a customer and each line is a call between two customers. The network is very dense, a reflection of the small world of the social networks.

This study, which has analyzed around 9,000 million calls throughout almost a year period, is the first to identify these features of the communication process and to quantify their impact in the diffusion of information. “This is something very important in the processes such as the diffusion of commercial information, viral marketing and the market trends of products, but also in situations such as the spreading of rumours, opinions, policies, etc.”, explained one of the authors of this research, Esteban Moro,.

The study’s main conclusion, published in the scientific Journal, Physical Review E, is the finding that people communicate in bursts. In this way, our behaviour (in communication as well as in other activities) does not happen in a homogenous way over time, but rather there is universal behaviour in which there is no communication, followed by short intervals called bursts. “This aspect of human activity which has also been observed in other activities such as e-mail, web page visits and stock market operations governs communication between people,” , the researchers concluded. The effect of the bursts is that it slows down the information diffusion since the large periods of inactivity in the communication between two persons make it less likely that information is passed from one to the other. The study also highlights another important aspect of human communications: in group conversations, that is, although it is produced in bursts, these bursts happen at the same time among the members of the social group, which then accelerates information diffusion within these groups.

When, how much, and how do I communicate

The main objective of the research is to try to understand the temporal pattern of communication among persons in a social network. “As opposed to the static vision of a social network (who I interact with), our study seeks to understand when and how these social relations are produced,” Professor Esteban Moro elaborated. And with two purposes, the first being, to see if relations in a social network can be quantified better, that is, determine if the communication rhythm between two persons allows us to know something about the “strength” or characteristics of the relation (family member, acquaintance, friend, colleague, etc..); and the second, to investigate the impact of these rhythms on the propagation of information in social networks, in processes such as viral marketing, product recommendations, etc.

Source: Universidad Carlos III de Madrid – Oficina de Información Científica