A meta-analysis of studies measuring blood concentrations of zinc in some 1,600 depressed subjects and 800 control subjects has found that zinc concentrations were significantly lower in the patients with depression. And in the studies that measured depressive symptoms, greater depression severity was associated with a greater relative zinc deficiency. The senior researcher was Krista Lanctot, Ph.D., of the University of Toronto, and results are published in Biological Psychiatry.

A meta-analysis of studies measuring blood concentrations of zinc in some 1,600 depressed subjects and 800 control subjects has found that zinc concentrations were significantly lower in the patients with depression. And in the studies that measured depressive symptoms, greater depression severity was associated with a greater relative zinc deficiency. The senior researcher was Krista Lanctot, Ph.D., of the University of Toronto, and results are published in Biological Psychiatry.

What the results mean from a clinical viewpoint, however, remains to be determined, the researchers point out. Since the literature on zinc and depression is largely limited to case-control and cross-sectional studies, it is not known whether depression creates a zinc deficiency or a zinc deficiency helps set the stage for depression. Zinc is an essential nutrient with multiple biological functions.

It is possible that depression creates a zinc deficiency, the researchers suggest, since appetite changes are a common component of major depression. One study of subjects with the disorder identified trends between lower zinc concentrations and weight loss and anorexia symptoms. On the other hand, a zinc deficiency can induce depressive-like behaviors in animals, which in turn can be reversed by zinc supplements, the researchers point out. Thus “the potential benefits of zinc supplementation in depressed patients warrant further investigation,” they note.

A wide variety of foods contain zinc. Oysters contain more zinc per serving than any other food, but red meat and poultry provide the majority of zinc in the American diet. Other good food sources include beans, nuts, certain types of seafood (such as crab and lobster), whole grains, fortified breakfast cereals, and dairy products.

A comprehensive overview of depression and how to offer optimal care to depressed patients can be found in the new American Psychiatric Publishing book, Clinical Guide to Depression and Bipolar Disorder: Findings From the Collaborative Depression Study. For more on treating depression, see Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Roadmap for Effective Care.

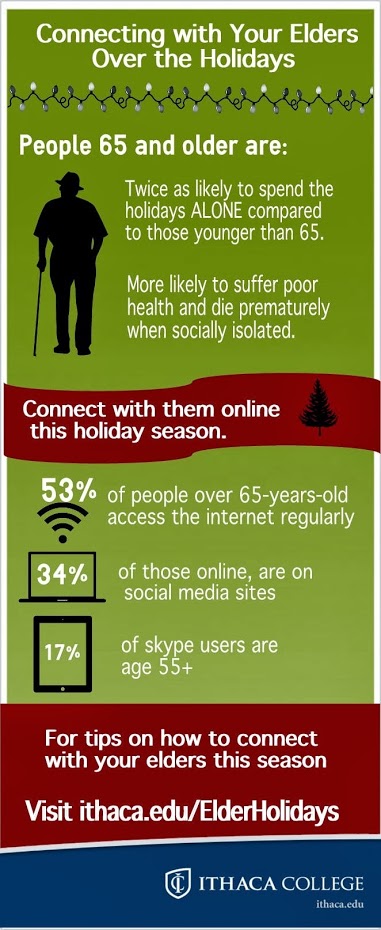

People over 65-years-old are twice as likely to spend the holidays alone compared to those less than 65. Bad weather, increased noise and crowds, and health challenges may make it more difficult for loved ones from older generations to travel.

People over 65-years-old are twice as likely to spend the holidays alone compared to those less than 65. Bad weather, increased noise and crowds, and health challenges may make it more difficult for loved ones from older generations to travel.

Dr. Paris has been a member of the McGill psychiatry department since 1972. Since 1994, he has been a full Professor, and served as Department Chair from 1997 to 2007. Dr. Paris is currently a Research Associate at the SMBD-Jewish General Hospital, and heads personality clinics at two hospitals. He is also Editor-in-Chief of the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Dr. Paris has 185 peer-reviewed articles, and is the author of 17 books and 44 book chapters. Dr. Paris is an educator who has won awards for his teaching.

Dr. Paris has been a member of the McGill psychiatry department since 1972. Since 1994, he has been a full Professor, and served as Department Chair from 1997 to 2007. Dr. Paris is currently a Research Associate at the SMBD-Jewish General Hospital, and heads personality clinics at two hospitals. He is also Editor-in-Chief of the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Dr. Paris has 185 peer-reviewed articles, and is the author of 17 books and 44 book chapters. Dr. Paris is an educator who has won awards for his teaching.