Published: August 12, 2010

Sons who have fond childhood memories of their fathers are more likely to be emotionally stable in the face of day-to-day stresses, according to psychologists who studied hundreds of adults of all ages.

Sons who have fond childhood memories of their fathers are more likely to be emotionally stable in the face of day-to-day stresses, according to psychologists who studied hundreds of adults of all ages.

Psychology professor Melanie Mallers, PhD, of California State University-Fullerton presented the findings Thursday at the 118th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association.

“Most studies on parenting focus on the relationship with the mother. But, as our study shows, fathers do play a unique and important role in the mental health of their children much later in life,” Mallers said during a symposium focusing on social relationships and well-being. [continue reading…]

Published: August 11, 2010

A great piece in Slate from Alan E. Kazdin and Carlo Rotella

A great piece in Slate from Alan E. Kazdin and Carlo Rotella

You work and work to provide for your kids, and that puts you under a lot of stress. Job insecurity, maybe some mortgage problems, and other common afflictions of the times only increase the pressure. You find yourself taking it out on your family—the kids, your spouse, the cat, any unfortunate who gets in your way. When you’re home and not obsessively checking your e-mail, you lose your temper, you snap and yell and brood, you run alternately too hot (angry and aggressive, spoiling for a fight) and too cold (withdrawn and distant, a forbidding stone-face). You’ll admit that you’re hard to be around, but look, life is tough and you’re knocking yourself out without much in the way of thanks or respite to make enough money to feed and house the kids, and that’s what matters most, right? link to read more

Source: Slate

When people are under chronic stress, they tend to smoke, drink, use drugs and overeat to help cope with stress. These behaviors trigger a biological cascade that helps prevent depression, but they also contribute to a host of physical problems that eventually contribute to early death. [continue reading…]

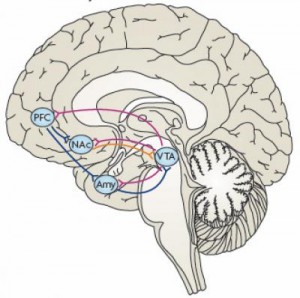

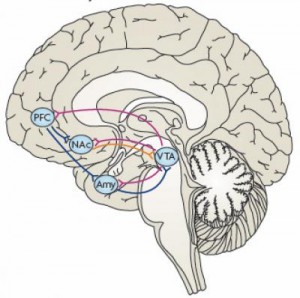

The transcription factor deltaFosB mediates resilience in the nucleus accumbens, hub of the brain’s reward circuit. It is the target of an intensive high tech screening for small molecules that tweak it, which could lead to a new class of resilience-boosting antidepressants.

cientists have discovered a mechanism that helps to explain resilience to stress, vulnerability to depression and how antidepressants work. The new findings, in the reward circuit of mouse and human brains, have spurred a high tech dragnet for compounds that boost the action of a key gene regulator there, called deltaFosB.

A molecular main power switch – called a transcription factor – inside neurons, deltaFosB turns multiple genes on and off, triggering the production of proteins that perform a cell’s activities.

“We found that triggering deltaFosB in the reward circuit’s hub is both necessary and sufficient for resilience; it protects mice from developing a depression-like syndrome following chronic social stress,” explained Eric Nestler, M.D., of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, who led the research team, which was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). [continue reading…]

Sons who have fond childhood memories of their fathers are more likely to be emotionally stable in the face of day-to-day stresses, according to psychologists who studied hundreds of adults of all ages.

Sons who have fond childhood memories of their fathers are more likely to be emotionally stable in the face of day-to-day stresses, according to psychologists who studied hundreds of adults of all ages.