Published: December 21, 2011

Image: Stockxpert

We know a lot about the links between a pregnant mother’s health, behavior, and moods and her baby’s cognitive and psychological development once it is born. But how does pregnancy change a mother’s brain? “Pregnancy is a critical period for central nervous system development in mothers,” says psychologist Laura M. Glynn of Chapman University. “Yet we know virtually nothing about it.” Glynn and her colleague Curt A. Sandman, of University of the California Irvine, are doing something about that. Their review of the literature in Current Directions in Psychological Science, a journal published by the Association for Psychological Science, discusses the theories and findings that are starting to fill what Glynn calls “a significant gap in our understanding of this critical stage of most women’s lives.”

At no other time in a woman’s life does she experience such massive hormonal fluctuations as during pregnancy. Research suggests that the reproductive hormones may ready a woman’s brain for the demands of motherhood—helping her becomes less rattled by stress and more attuned to her baby’s needs. Although the hypothesis remains untested, Glynn surmises this might be why moms wake up when the baby stirs while dads snore on. Other studies confirm the truth in a common complaint of pregnant women: “Mommy Brain,” or impaired memory before and after birth. “There may be a cost” of these reproduction-related cognitive and emotional changes, says Glynn, “but the benefit is a more sensitive, effective mother.” [continue reading…]

Published: December 6, 2011

Older women with weaker circadian rhythms, who are less physically active or are more active later in the day are more likely to develop dementia or mild cognitive impairment than women who have a more robust circadian rhythm or are more physically active earlier in the day. That’s the finding of a new study in the latest issue of the Annals of Neurology.

Older women with weaker circadian rhythms, who are less physically active or are more active later in the day are more likely to develop dementia or mild cognitive impairment than women who have a more robust circadian rhythm or are more physically active earlier in the day. That’s the finding of a new study in the latest issue of the Annals of Neurology.

“We’ve known for some time that circadian rhythms, what people often refer to as the “body clock”, can have an impact on our brain and our ability to function normally,” says Greg Tranah, PhD., a scientist at the California Pacific Medical Center Research Institute – part of the Sutter Health network – and the lead author of the study. “What our findings suggest is that future interventions such as increased physical activity or using light exposure interventions to influence circadian rhythms, could help influence cognitive outcomes in older women.”

The researchers collected data on activity and circadian rhythm from 1,282 healthy women, all over the age of 75, who were taking part in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. All the women underwent a series of neuropsychological tests to ensure they had no evidence of cognitive or brain problems. At the end of five years 15 percent of the women had developed dementia and 24 percent had some form of mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Those women who had weaker circadian rhythm activity, lower levels of activity, or whose peak level of activity was later in the day, were at highest risk of developing dementia or MCI. [continue reading…]

Published: November 16, 2011

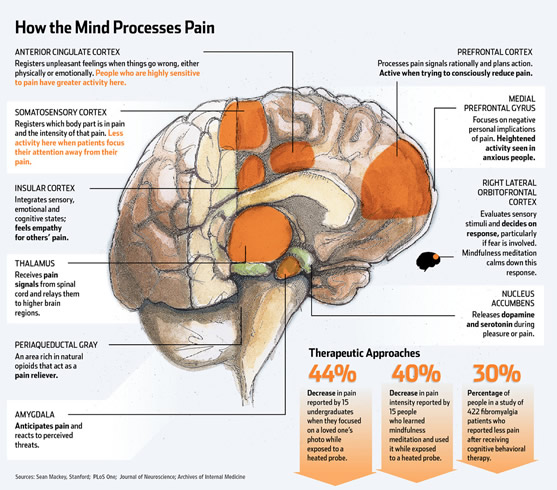

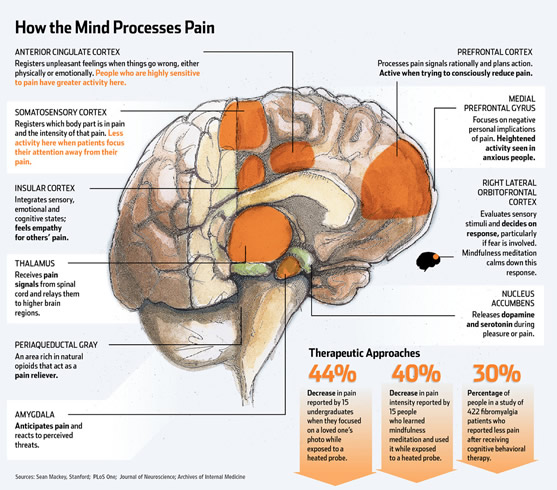

Source: Sean Mackey, Stanford. Plos One, Journal Neuroscience: Archives of Internal Medicine

Melinda Beck’s Wall Street Journal article Rewiring the Brain to Ease Pain looks at how you think about pain can have a major impact on how it feels.

That’s the intriguing conclusion neuroscientists are reaching as scanning technologies let them see how the brain processes pain.

That’s also the principle behind many mind-body approaches to chronic pain that are proving surprisingly effective in clinical trials.

Some are as old as meditation, hypnosis and tai chi, while others are far more high tech. In studies at Stanford University’s Neuroscience and Pain Lab, subjects can watch their own brains react to pain in real-time and learn to control their response—much like building up a muscle. When subjects focused on something distracting instead of the pain, they had more activity in the higher-thinking parts of their brains. When they “re-evaluated” their pain emotionally—”Yes, my back hurts, but I won’t let that stop me”—they had more activity in the deep brain structures that process emotion. Either way, they were able to ease their own pain significantly, according to a study in the journal Anesthesiology last month.

Link to read article

Source: Wall Street Journal

Published: November 10, 2011

If future research can pinpoint why an excessive number of brain cells are there in the first place, it will have a large impact on understanding autism, and perhaps on developing new treatments, said Courchesne.

Andrew Carnie, Autumn Twist

.

Having a big brain may seem like an advantage at first thought, but new research indicates that it may be one symptom of autism. Boys with autism displayed an abnormally large number of neurons in the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain involved in social, communication, and cognitive development, according to lead researcher Eric Courchesne, Ph.D., of the University of California, San Diego. Courchesne and colleagues reported in the November 9 JAMA that the brains of seven boys with autism contained 67 percent more cortical cells than brains of boys without autism. Those cells develop in great numbers early in fetal development but are normally removed during the last trimester.

Source: American Psychiatric Association