Published: October 9, 2011

A new study of the brain explains why some of us are better than others at remembering what really happened.

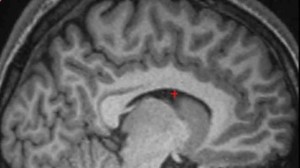

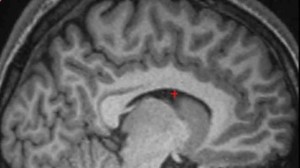

A structural variation in a part of the brain may explain why some people are better than others at distinguishing real events from those they might have imagined or been told about, researchers have found.

A structural variation in a part of the brain may explain why some people are better than others at distinguishing real events from those they might have imagined or been told about, researchers have found.

The University of Cambridge scientists found that normal variation in a fold at the front of the brain called the paracingulate sulcus (or PCS) might explain why some people are better than others at accurately remembering details of previous events -such as whether they or another person said something, or whether the event was imagined or actually occurred. The research was published today, 05 October, in the Journal of Neuroscience.

This brain variation, which is present in roughly half of the normal population, is one of the last structural folds to develop before birth and for this reason varies greatly in size between individuals in the healthy population. The researchers discovered that adults whose MRI scans indicated an absence of the PCS were significantly less accurate on memory tasks than people with a prominent PCS on at least one side of the brain. Interestingly, all participants believed that they had a good memory despite one group’s memories being clearly less reliable. [continue reading…]

Published: September 26, 2011

Vitamin B12 is found in meat, fish and dairy,

lder people with low blood levels of vitamin B12 markers may be more likely to have lower brain volumes and have problems with their thinking skills, according to researchers at

Rush University Medical Center.

The results of the study are published in the Sept. 27 issue of Neurology, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

Foods that come from animals, including fish, meat, especially liver, milk, eggs and poultry are usual sources of vitamin B12.

The study involved 121 older residents of the South side of Chicago who are a part of the Chicago Health and Aging Project (CHAP), which is a large, ongoing prospective Rush a biracial cohort of 10,000 subjects over the age of 65.

The 121 participants had blood drawn to measure levels of vitamin B12 and B12-related markers that can indicate a B12 deficiency. The same subjects took tests measuring their memory and other cognitive skills.

An average of four-and-a-half years later, MRI scans of the participants’ brains were taken to measure total brain volume and look for other signs of brain damage.

Having high levels of four of five markers for vitamin B12 deficiency was associated with having lower scores on the cognitive tests and smaller total brain volume. [continue reading…]

Published: September 9, 2011

Managing other people at work triggers structural changes in the brain, protecting its memory and learning centre well into old age.

UNSW researchers have, for the first time, identified a clear link between managerial experience throughout a person’s working life and the integrity and larger size of an individual’s hippocampus – the area of the brain responsible for learning and memory – at the age of 80.

The findings refine our understanding of how staying mentally active promotes brain health, potentially warding off neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s. The study was presented this week at the Brain Sciences UNSW symposium Brain Plasticity –The Adaptable Brain.

The Symposium focused on research that is revealing the brain’s ability to repair, rewire and regenerate itself, overturning scientific dogma that the brain is “hard-wired”. [continue reading…]

Published: August 17, 2011

© istockphoto

n unexpected discovery has led scientists to open an intriguing new window into the human brain, via the visual system.

Their finding may have implications for better understanding of states such as sleep, epilepsy and anaesthesia say the research team leaders Dr Sam Solomon and Professor Paul Martin of The Vision Centre and The University of Sydney.

Potentially it could open up a new pathway for manipulating brain rhythms to manage disorders such as insomnia and epilepsy, the team speculate in an article published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA.

“It was purely a chance observation we made while we were activating the three cell layers of the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN), which is the part where the optic nerve actually connects to the brain,” Prof. Martin recounts.

Two of these layers are linked with our ability to perceive edges and movement, he explains. The third, koniocellular or ‘K’ layer, is much more primitive – part of our deep evolutionary ancestry – and its function is still mysterious.“When we stopped applying a stimulus, two of the three layers ceased to respond while the K layer continued to pulse, slowly and rhythmically – like a sleeping brain.”

At the suggestion of a colleague, the research team then compared the signal from the K cells to an EEG readout from the brain itself: “To our surprise and delight we found the two were marching in time,” Dr Solomon says. The observation has provided physical evidence to support a scientific theory that the more primitive parts of the brain serve as regulators for the more advanced parts, responsible for conscious thought and feelings.It could also lead to a deeper scientific understanding of the nature of sleep and unconsciousness. [continue reading…]

A structural variation in a part of the brain may explain why some people are better than others at distinguishing real events from those they might have imagined or been told about, researchers have found.

A structural variation in a part of the brain may explain why some people are better than others at distinguishing real events from those they might have imagined or been told about, researchers have found.